George Sanders, Arizona Man, Gets Probation In Mercy Killing

By BRIAN SKOLOFF

03/30/13 04:12 AM ET EDT

George Sanders, center, is joined by his attorney Janey Henze Cook,

right, outside a Phoenix courtroom, Friday, March 29, 2013. The

86-year-old, who carried out a mercy killing by shooting his ailing wife

and high school sweetheart in the head, was sentenced Friday to

probation after an emotional hearing where family members tearfully

spoke on his behalf. (AP Photo/Brian Skoloff)

"My grandfather lived to love my grandmother, to serve and to make her feel as happy as he could every moment of their life," Sanders' grandson, Grant, told the judge, describing the couple's life together as "a beautiful love story."

"I truly believe that the pain had become too much for my grandmother to bear," he said, while Sanders looked on during the sentencing hearing Friday and occasionally wiped his eyes with a tissue as relatives pleaded tearfully for mercy.

Sanders was arrested last fall after he says his wife, Virginia, 81, begged him to kill her. He was initially charged with first-degree murder, but pleaded guilty to manslaughter in a deal with prosecutors. Still, he faced a sentence of up to 12 years.

His wife, whose family called her Ginger, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1969, and was forced into a wheelchair soon after. She and Sanders, a World War II veteran, moved from Washington state in the 1970s for Arizona's warm, dry climate.

George Sanders became her sole caregiver. He cooked for her, cleaned the house, did laundry, put on her makeup and would take her to the beauty salon where he'd hold her hands up so she could get her nails done.

Eventually, though, his own health deteriorated. He had a pacemaker put in, and Virginia was diagnosed with gangrene on her foot. She was set to be admitted to a hospital, then likely a nursing home where she would spend the remainder of her life.

"It was just the last straw," Sanders told a detective during his interrogation shortly after the shooting at the couple's home in a retirement community outside Phoenix. "She didn't want to go to that hospital ... start cutting her toes off."

He said his wife begged him to kill her. "I said, `I can't do it honey,'" he told the detective. "She says, `Yes you can.'"

Sanders then got his revolver and wrapped a towel around it so the bullet wouldn't go into the kitchen. "She says, `Is this going to hurt?' and I said, `You won't feel a thing,'" he said.

"She was saying, `Do it. Do it. Do it.' And I just let it go," Sanders added.

In court Friday, as Sanders awaited his fate, his son told the judge the family never wanted him to be prosecuted.

"I want the court to know that I loved my mother dearly," Steve Sanders said. "But I would also like the court to know that I equally love my father."

Breaking down at times in tears, he explained how his parent's spent 62 years together, and his father took care of his mother day in and day out.

"I fully believe that the doctor's visits, the appointments, the medical phone calls and the awaiting hospital bed led to the decision that my parents made together," he said. "I do not fault my father.

"A lot of people have hero figures in their life, LeBron James ... some world class figures ... but I have to tell you my lifelong hero is my dad," he told the judge, sobbing.

George Sanders, wearing khakis and a white sport coat, spoke for only a minute about his deep love for his wife.

"Your honor, I met Ginger when she was 15 years old and I've loved her since she was 15 years old. I loved her when she was 81 years old," he said, trembling.

"It was a blessing, and I was happy to take care of her,"

Sanders continued. "I am sorry for all the grief and pain and sorrow I've caused people."

Prosecutor Blaine Gadow also asked the judge not to sentence Sanders to prison, instead recommending probation.

"The family very much loved their mother," Gadow said, noting the "very unique, difficult circumstances of this case."

"I don't know where our society is going to go with cases like this, judge," he added. "At this point in time, what Mr. Sanders did was a crime." However, he said, "No one in the courtroom has forgotten the victim in this case."

As family members took their seats and Sanders stood trembling at the podium in the courtroom, Judge John Ditsworth spoke softly, staring at the defendant from just a few feet away then sentenced him to two years of unsupervised probation.

Ditsworth said his decision "tempers justice with mercy."

"It is very clear that he will never forget that his actions ended the life of his wife," Ditsworth said.

The 28-year-old

The 28-year-old  what the 90's model Cadillac's asking price was or what discount Frantzen would be receiving for pleasuring the seller.

what the 90's model Cadillac's asking price was or what discount Frantzen would be receiving for pleasuring the seller.

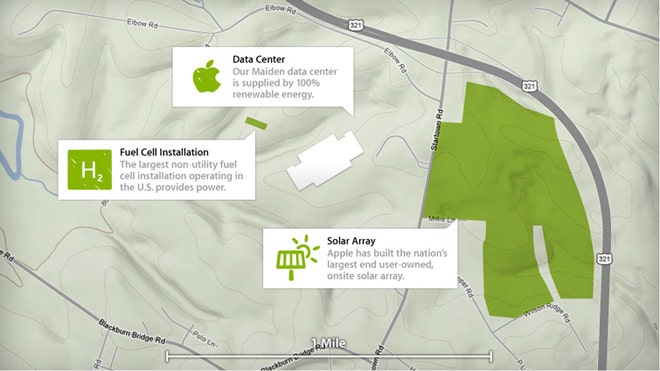

, announcing plans to shoot for 100 percent renewable power sources. The 100-acre, 20-megawatt facility can produce 42 million kWh of renewable energy each year, Apple said.

, announcing plans to shoot for 100 percent renewable power sources. The 100-acre, 20-megawatt facility can produce 42 million kWh of renewable energy each year, Apple said.

Pentagon officials say that a plan being pushed

Pentagon officials say that a plan being pushed